Mobile Media and the Paleolithic

- Grant Wythoff

An article in progress, previously presented at the New Apparatus Theory panel at SLSA-Turin 2014, Archaeologies of Film and Media, Bradford, and the Heyman Center for the Humanities. As we begin to take up new objects of study, how do humanists—largely trained in the analysis of text—apply their expertise to the interpretation of artifacts? What are the unique forms of evidence and argumentation found in media studies and digital humanities?

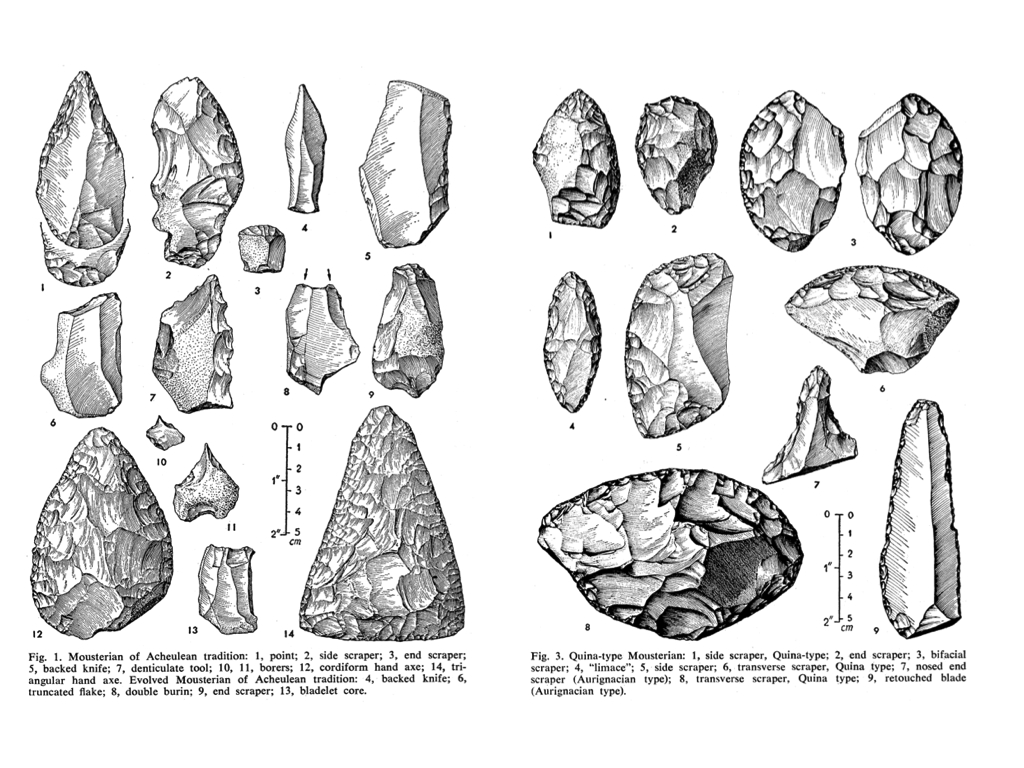

In the mid-1950s, a collection of Neanderthal artifacts was unearthed in the southwest of France, kicking off one of the most famous debates over the study of cultural transmission through the archaeological record. At a time before the development of chronometric techniques like radiocarbon dating that would allow later archaeologists to definitively order these artifacts in time and space, the Mousterian debate centered on the question of how we can extrapolate history from the formal properties of a technical object.

This project attempts to put debates from the history of archaeology into conversation with an exciting new field in media studies known as media archaeology. Media archaeology has thus far been informed by Michel Foucault’s (largely metaphorical) use of the term archaeology to denote an inquiry into “the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events.” But I will argue here that the traditional field of archaeology, its primary concern being the study of how objects mediate our relationship to the past, has much to offer a media archaeology.

By focusing on the two principal figures in this debate – the established French archaeologist and sometime science fiction novelist François Bordes and the upstart American Lewis Binford – I attempt to draw larger conclusions about how we both experience and interpret the artifacts around us.