Plain Text

- Dennis Yi Tenen

While I write these introductory remarks, a ceiling-mounted smoke detector in my kitchen emits a loud noise every three minutes or so. A pleasant female voice announces also “low battery.” This is, I learn, a precaution stipulated by US National Fire Alarm Code 72-108 11.6.6 (2013). The clause requiring a “distinct audible signal before the battery is incapable of operating” is encoded into the device. The smoke detector literally embodies that piece of legislation in its circuitry. We thus obtain a condition where two meanings of code—as governance and machine instruction—coincide. Code equals code.

I am at home, but I also receive a notification of the alarm on my mobile phone. Along with monitoring apps that help make my home “smarter,” the phone contains most of my library. I often pick it up to read a book. The phrase “reading a book,” however, obscures a number of metaphors for a series of odd actions. The “book” is a small, thin black rectangle: three inches wide, five inches tall, and barely a few millimeters thick. A slab of polished glass covers the front of the device, where the tiny eyes of a camera and a light sensor also protrude. At the back, made of smooth soft plastic, we find another, larger camera. At the foot of the device, a grid of small perforations indicates breathing room for a speaker and several microphones. To “open” a book I touch the glass. The machine recognizes my fingerprint. I then tap and poke at the surface until I find a small image that represents both my library and book store, where I can “buy” and “borrow” books. Buying or borrowing books does not, however, involve the possession of physical objects. Rather, I agree to a license that grants limited access to data, which the software then assembles into something resembling a book on screen. I tap again to begin reading. The screen dims to match room ambiance as it fills up with words. A passage on the first page appears underlined: other readers in my social circle must have found it notable. I swipe across the glass surface to turn a “page.” The device emits a muffled rustle to reinforce the pretense of manipulating paper. The image curls ever so slightly as another “page” slides into view. My tiny library metaphor contains hundreds of such page metaphors.

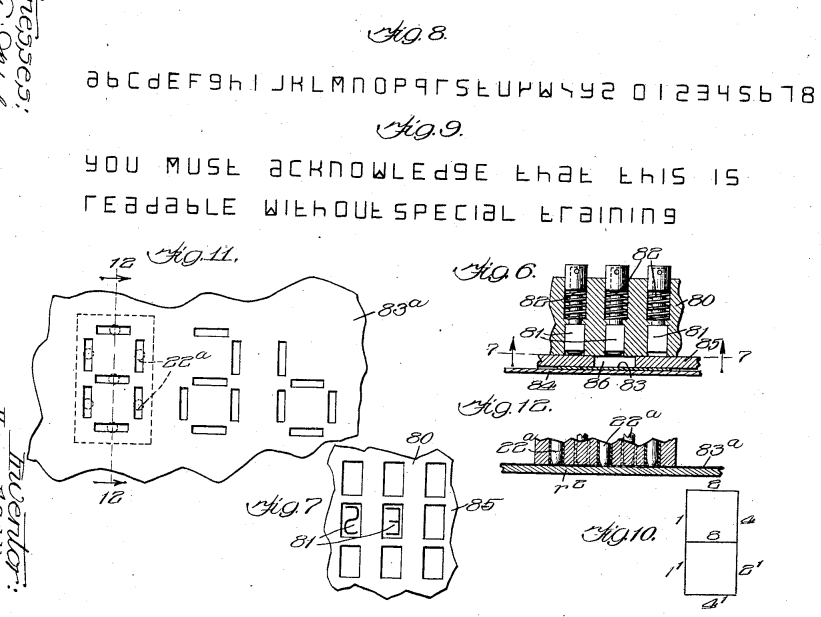

Despite appearances, the electronic metaphor-making device on my desk has more in common with smoke detectors than it does with several paper volumes scattered on my desk. The electronic book and smoke alarm contain printed circuit boards, capacitors, and resistors. Both draw electric current. Both require firmware updates and both are governed by codes, political and computational. Smoke alarms and mobile phones connect to the internet. They communicate with distant data centers and with each other. Yet, I continue to “read” these devices as if they were familiar, immutable, and passive objects: just books. I think of them as intimate artifacts—friends even—wholly known to me, comforting, and warm. The electronic book is none of those things. Besides prose, it keeps my memories, pictures, words, sounds, and thoughts. It records my reading, sleeping, and consumption habits. It tries to sell me things, showing me advertisements for cars, jewelry, and pills. It comes with a manual and terms of service. It is my confidant, my dealer, my spy. Plain Text concerns the nature of digital inscription—the material trace that gives rise to textual phenomena, and, more broadly, to all cultural artifacts in which computers mediate. We find ourselves today in an unprecedented, since the Middle Ages, position of selective asemiosis: the loss of signification. Many contemporary texts—like poems inscribed into bacteria and encrypted software—exist simply beyond the reach of human senses.1 Other forms of writing are illegible by design, in ways that prevent access or comprehension. Increasingly, we write not in the sense of making marks on paper but in simulation. Key presses leave lasting traces in computer memory, which then appear on screen redoubled and ephemeral. On disk, marks endure in a form legible only to those who possess the specialized tools and training necessary to decipher them.

I appeal to the idea of “plain text” in the title of this book to signal an affinity with a particular mode of computational meaning-making. Plain text identifies a file format and frame of mind. As file format, it contains nothing but a “pure sequence of character codes.” Plain text stands in opposition to “fancy text,” “text representation consisting of plain text plus added information.”2 In the tradition of American textual criticism, “plain text” alludes to an editorial method of text transcription which is both “faithful to the text of its source” and is “easier to read than the original document.”3 Combining these two traditions, I mean to build a case for a kind of a systematic minimalism when it comes to our use of computers—a minimalism that privileges access to source materials, ensuring legibility and comprehension. I do so in contrast with other available modes of human-computer interaction, which instead maximize system-centric ideals like efficiency, speed, performance, or security.

The title further identifies an interpretive stance one can assume in relation to the making and the unmaking of literary artifacts. Besides visible content, all contemporary documents carry with them a layer of hidden information. Originally used for typesetting, that layer affects more than innocuous document attributes like “font size” or “line spacing.” Increasingly, devices that mediate literary activity also embody governing structures. For example, the Digital Millennium Copyright act, passed in the United States in 1996, goes beyond written injunction to require in some cases the management of digital rights (DRM) at the level of hardware. An electronic book governed by DRM may subsequently prevent the reader from copying or sharing stored content, even for the purposes of academic study.4 In some situations, the device may collect reader activity.

Machine instruction thus embodies new forms of technological control. To speak truth to power—to retain a civic potential for critique—we must therefore perceive the mechanisms of its codification. Critical theory cannot otherwise endure apart from material contexts of textual production, which today emanate from the fields of computer science and software engineering. Conversely, a tighter coupling with the critical tradition can reveal technology’s often occluded political implications. To create a novel algorithm that predicts crime by analyzing one’s reading habits, for example, is also to invite the dystopian possibility of thought policing, unless, that is, such algorithms remain legible, in public view, and under continual counter-scrutiny. A vibrant discursive practice of textual exegesis is crucial for the preservation of whatever ideals that demand a literate populace.

-

See Bök, “The Xenotext Works.” and Bök, The Xenotext: “I have been striving to write a short verse about language and genetics, whereupon I use a ‘chemical alphabet’ to translate this poem into a sequence of DNA for subsequent implantation into the genome of a bacterium (in this case, a microbe called Deinococcus radiodurans—an extremophile, capable of surviving, without mutation, in even the most hostile milieus, including the vacuum of outer space).” ⤻

-

Unicode Consortium, “The Unicode Standard,” 9–10. ⤻

-

Cook, “Some Considerations in the Concept of Pre-Copy-Text.” ⤻

-

See Ku, “Critique of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s Exception on Encryption Research.”; Ginsburg, “Legal Protection of Technological Measures Protecting Works of Authorship.”; and Fry, “Circumventing Access Controls Under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.” ⤻