Middlemarch Critical Histories

- Jonathan Reeve

- Milan Terlunen

- Sierra Eckert

Text reuse detection technology and approximate text matching have made possible the large-scale computational identification of intertextuality. These technologies have often been used in plagiarism detection and in studies of journalistic text reuse. Fewer studies, however, have applied these methods to humanities research. We present a method for quantifying the critical reception history of a source text by analyzing the precise location, density and chronology of its citations.

Our work builds on a recent set of digital humanities projects that use text reuse detection in order to study the afterlife of texts through textual quotation. The Viral Texts project and Digital Breadcrumbs of Brothers Grimm take algorithmic approaches to studying text reuse and circulation in their respective fields of research: nineteenth-century popular press and folklore. In both projects, the focus is on using text reuse detection to uncover hidden networks of reuse—the reprinting of short news items and the re-use of motifs or minimal narrative units in folklore—in corpora without standardized conventions of citation. Our project seeks to take this work a step further, by applying a similar method in a different area of cultural production where more standardized citation conventions already exist: academic citations. We draw on the work of Dennis Tenen—in using extracted citations to critically visualize the “knowledge domain” of Comparative Literature—and a recent project by JSTOR Labs that uses the text of Shakespeare’s plays and the U.S. Constitution to visualize the scholarship surrounding passages in those sets of texts.1 Like these projects, we hope to leverage the explicit and institutionalized nature of academic citation in studying text-reuse patterns, using text reuse to ask questions of critical attention in canon formation. By focusing initially on a single text in order to ask about its critical reception history, we hope to provide new methods for studying not only text-reuse patterns, but the sociology of citation practices—studying changes in when, how, and what critics cite from a given text.

In applying these methods to literary scholarship, we’ve chosen to start on a relatively small scale. George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch is an ideal test case, due to its length, copyright status, stable editorial history and canonicity. Perhaps most appropriately for this study, Middlemarch is known for its narrator’s wise generalizations—highly quotable fragments that have been featured in more than one Victorian volume of George Eliot’s sayings. For the full project we are working with JSTOR Labs to assemble a corpus of all 6,500 articles on Middlemarch in their collection. The figures below display preliminary results with a smaller 483-sample corpus.

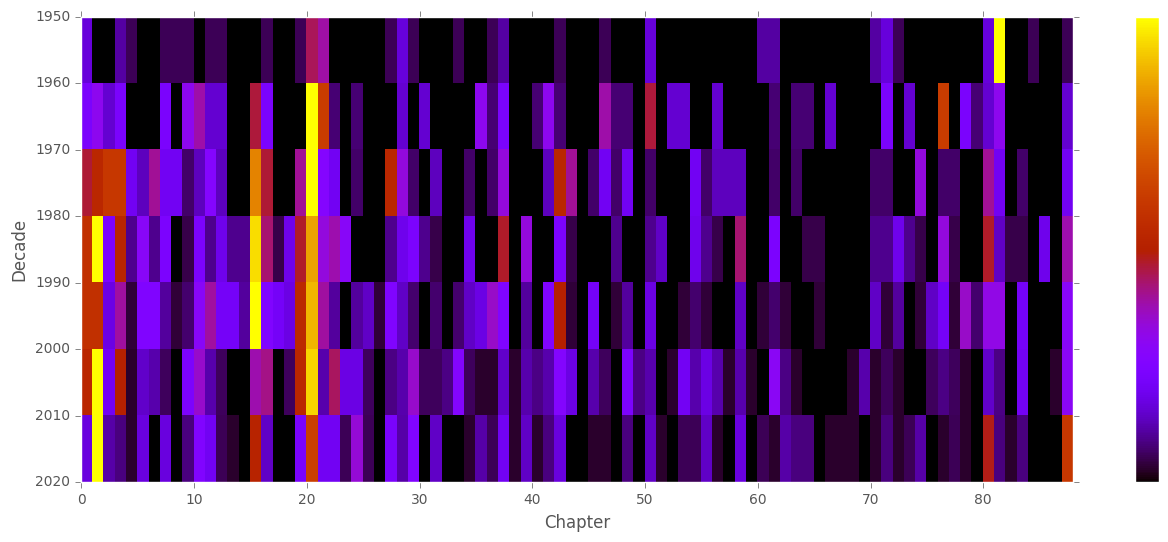

At the largest scale, Figure 1 shows the frequency of citations across the whole of Middlemarch as a heat map segmented by decade, with yellow signifying the highest citation and black, no citations. Here, the novel is broken into 50 segments along the horizontal axis, and each segment is colored according to the number of times any part of its text has appeared in the critical literature. A number of overall trends are noticeable here. The very beginning and the end of the novel show the most numbers of quotations, followed by the first quarter of the novel. Overall, the second half of the novel, except for the ending, is significantly less quoted from than the first half.

Viewed chronologically, we see that critical interest in certain sections—as expressed in numbers of quotations—appears to shift over time. In the 1950s, most of the critical citation was of the end of the novel, at its climactic third-to-last section, but this interest has faded almost completely by the present day. At the same time, critical interest in the beginning of the novel seemed to be at a relative low point in the 1950s, but quickly became a highly quoted segment by the 1970s. This shift may represent a change in critical attention to the parts of the novel, shifting from the end of the novel at midcentury to the beginning of the novel, where it still appears to rest.

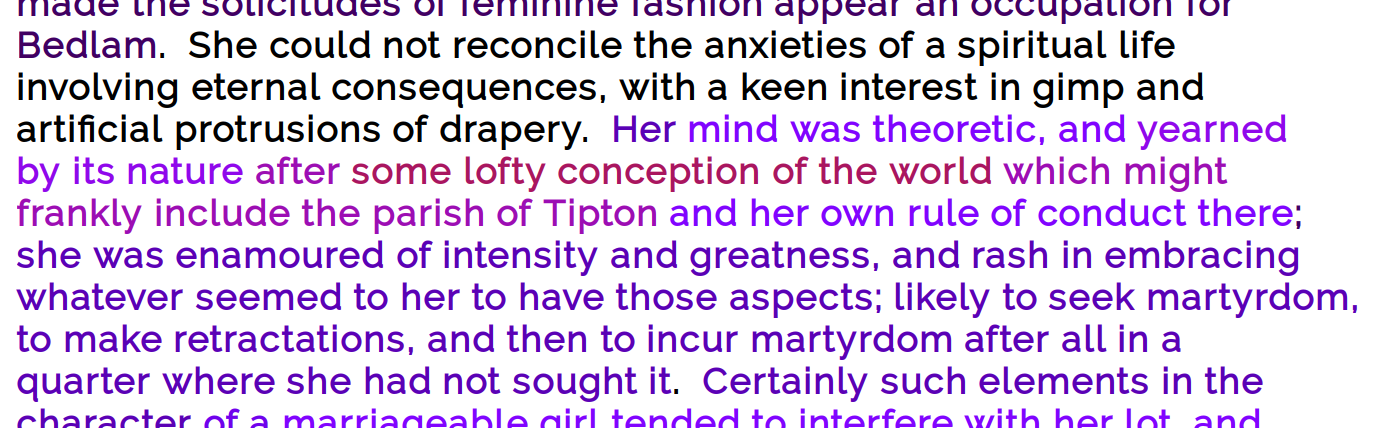

Figure 2 shows a finer grained analysis, no longer segmented by decade, displaying an excerpt from our paragraph-level text browser for Middlemarch. Here again, the color coding represents the number of quotations of each segment, ranging from unquoted black passages, to infrequently quoted purple and red passages and more frequently quoted yellow ones. In our sample, the somewhat abstract contrast between “spiritual life” versus “gimp” and “drapery” remains unquoted, whereas the short, punchy “Her mind was theoretic” has triggered numerous quotations, peaking with the stirring phrase “some lofty conception of the world”, before the frequency falls again slightly as the narrator describes how this character’s idealism clashes with the real world. This annotated edition could provide both scholars and students of literature with a way to read the novel for passages that have been most discussed in secondary literature, and for passages that have been critically neglected.

The potential applications of this methodology are numerous and wide-ranging. Firstly, this methodology can be used in any discipline to investigate the discipline’s theoretical history. As with the 1980 study of Wundt’s influence on the field of psychology,2 our methodology could rapidly and easily produce similar investigations for the influence of Saussure in linguistics, Bourdieu in sociology, Mead in anthropology, Beauvoir in feminist theory, and so on. Moreover, this analysis would be much more fine-grained, registering not only the frequency of works cited but also specific sections, passages and even key phrases within them.

In addition, we see particular relevance of our methodology to disciplines substantially engaged in questions of quotation and commentary. In theology, commentaries on sacred texts could be analysed in this way to give insights into the texts’ interpretive history. In philosophy, the citation of key texts in later periods could be used to assess the shifting priorities of subsequent generations of philosophers. Legal scholars, given the exceptional value placed on precedent in law, have long been interested in using digital technologies and studying citation practices (both of which underpin the recent Ravel project at Stanford University’s Law School), which our methodology would make even more granular (not just page numbers but exact phrases).

To return to literary studies, while our own initial project is focusing on academic literary criticism of the post-war period, the methodology could equally be applied to earlier aspects of literary reception. We are interested to examine whether patterns of citation change measurably since English literature is established as a discipline in the late nineteenth century. Going even further back, our methodology could equally be applied to quotations of literary works in non-academic formats, whether non-fiction (newspapers, journals, essays) or other literary works (citations of Shakespeare in Romantic poetry, say).

Our own next steps in this project will be to expand our corpus of quoted texts—the single texts whose citations we are tracing. Do similar patterns of citation apply to Eliot’s other novels? Do they apply to novels by Dickens, or by Austen? These analyses will allow us to begin to formulate general hypotheses about patterns of quotation within literary scholarship of recent decades, while also offering unprecedented insights into the works of each of these authors.

-

Dennis Tenen, “Digital Displacement,” in Futures of Comparative Literature, ed. Ursula K. Heise, Dudley Andrew, Alexander Beecroft, Jessica Berman, David Damrosch, Guillermina De Ferrari, César Domínguez, Barbara Harlow, and Eric Hayot (London: Routledge, forthcoming in 2017). ⤻

-

Brožek, Josef. “The Echoes of Wu.” ⤻