Distributed Agency in the Novel

- Dennis Yi Tenen

In this paper I discuss the question of institutional agency more narrowly, on the basis of a literary genre principally concerned with trans-human, organizational actors. The readings will occasion a model of agency more broadly, which besides its exploratory, theoretical potential will find its application in a method for extracting literary characters. State-of-the-art methods for detecting literary characters often rely on features such as named entities (i.e. Heathcliff), gender attributes, and evidence of direct speech or sentience.1 The house in Bleak House (1952–1853) by Charles Dickens, the wheat and the Railroad Commission in The Octopus (1901) by Frank Norris, and the airport in Arthur Hailey’s Airport (1968) are not characters by these measures. Yet we intuit them to act vitally and to exert an almost hypnotic influence on the action of the novel: “a strange beast that pertains to no one in particular and who is nobody’s responsibility.”2

Major spoiler alert: “This is Bleak House. This day I give this house its little mistress,” John says to Esther as the narrative gaze soars to observe the scene in its totality, describing, in a single majestic sweep of a sentence and paragraph, the orchards, the streams, the town nearby, the rooms inside, the colonnades, walls, and the furniture of the house, “the arrangement of all the pretty little objects […] my odd little ways everywhere.” “You should have married the airport, not me,” Cindy, the wife of the airport’s general manager (Mel), says bitterly to her often absent husband. “Ah, yes, the Wheat,” the narrator of The Octopus concludes:

As if human agency could affect this colossal power! What were these heated, tiny squabbles, this feverish, small bustle of mankind, this minute swarming of the human insect, to the great, majestic, silent ocean of the Wheat itself! Indifferent, gigantic, resistless, it moved in its appointed grooves. Men, Liliputians, gnats in the sunshine, buzzed impudently in their tiny battles, were born, lived through their little day, died, and were forgotten; while the Wheat, wrapped in Nirvanic calm, grew steadily under the night, alone with the stars and with God.

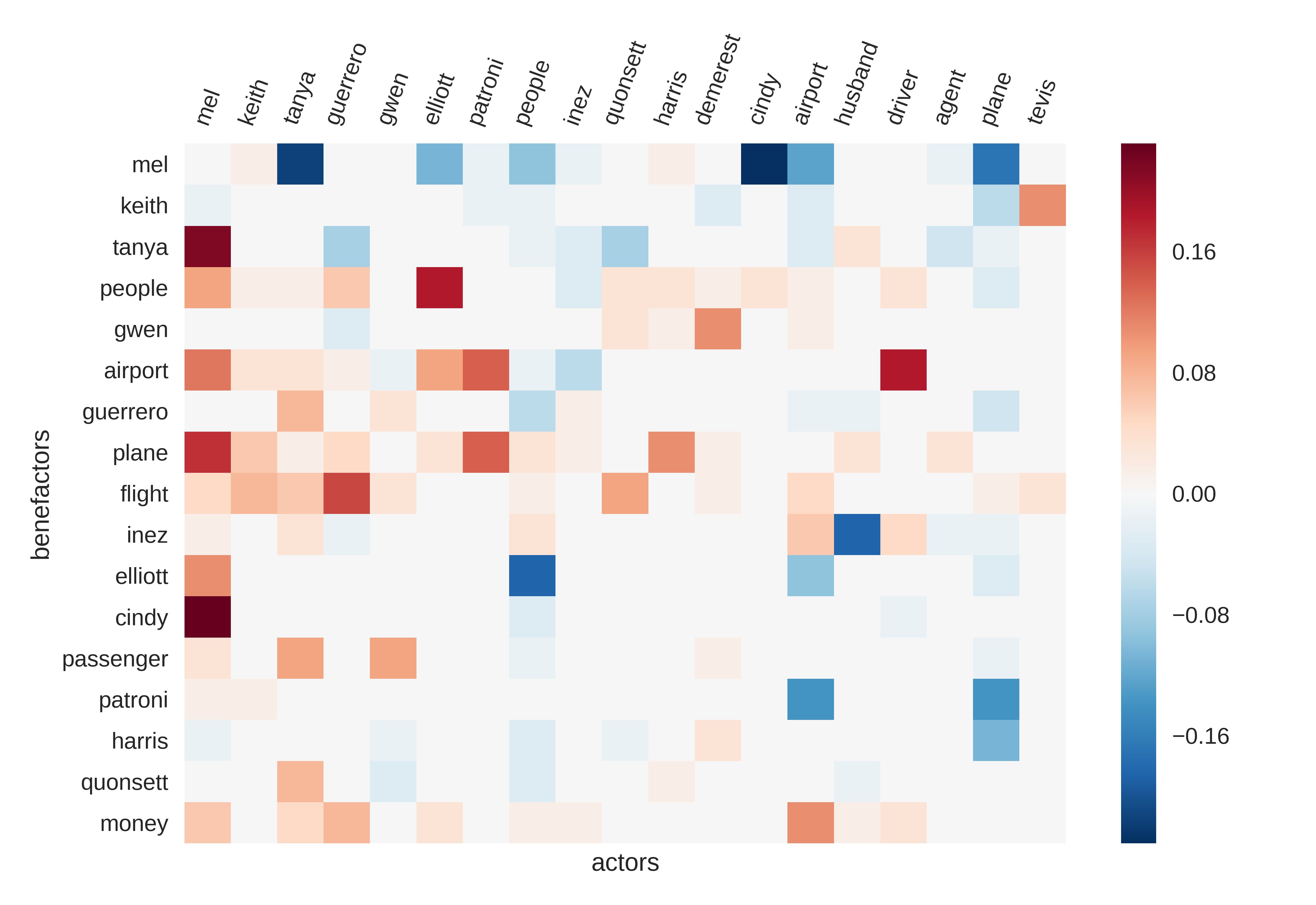

Such emergent senses of volition, characteristic of trans-human agents, presents a particular challenge to formalization. Our problem is two-fold: first, to conceptualize agency in a way that would encompass small bustles and large—Johns, Cindys, Mels, and Esthers, gnats and oceans of wheat, giants and lilliputians, bleak houses and their mistresses, airports and their general managers. Second, it would be helpful to be able to recognize a range of human and trans-human agents programmatically, both in order to discern a genre—an aggregation of texts—which does not simply address institutions thematically but in which institutions and natural forces play an active role. The former leads to a theory of character agency and the latter to a method for character extraction and analysis.

-

He, Barbosa, and Kondrak, “Identification of Speakers in Novels”; Coll Ardanuy and Sporleder, “Structure-Based Clustering of Novels”; Vala et al., “Mr. Bennet, His Coachman, and the Archbishop Walk into a Bar but Only One of Them Gets Recognized”; Iyyer et al., “Feuding Families and Former Friends.” ⤻

-

Latour, Reassembling the Social, 44. ⤻